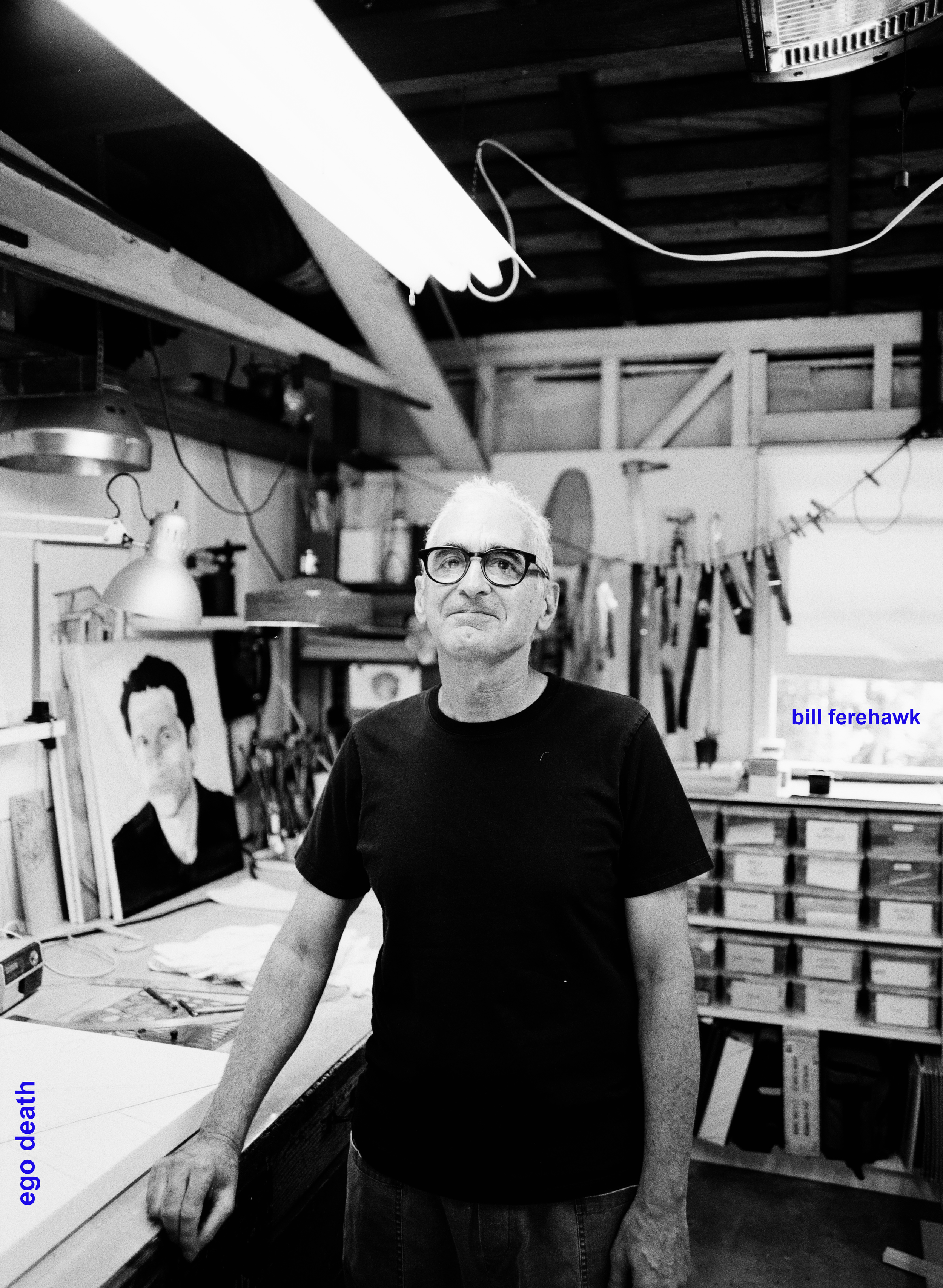

BILL FEREHAWK

I left that day feeling like I had made a big mistake.

I had practically met everyone at that art show. I was there supporting one of my closest friends, Ally (fellow Ego Death writer), on her poetry and photography composition. (Brilliant, might I add).

I remember seeing this painting.

It was the first piece, located right at the exhibit’s entrance. It featured a floating man, suspended in either elation or disorientation. I couldn’t tell. The colors were specific, unmistakably interesting.

…And I didn’t get a chance to shake the hand that held that paintbrush.

By the grace of faith, magic, or pure coincidence, I found myself, two weeks later, paired up with the artist at a community workshop.

Bill Ferehawk has been in my life ever since.

Within the first ten minutes of meeting, he offered me his Bolex 16mm camera to shoot with for a project I was figuring out how to direct. He had used it on a handful of experimental films.

He barely knew me.

He told me of his upbringing, his first-hand battles with mental health, and his heroic journey of becoming a self-made artist. I asked him if he was interested in an interview.

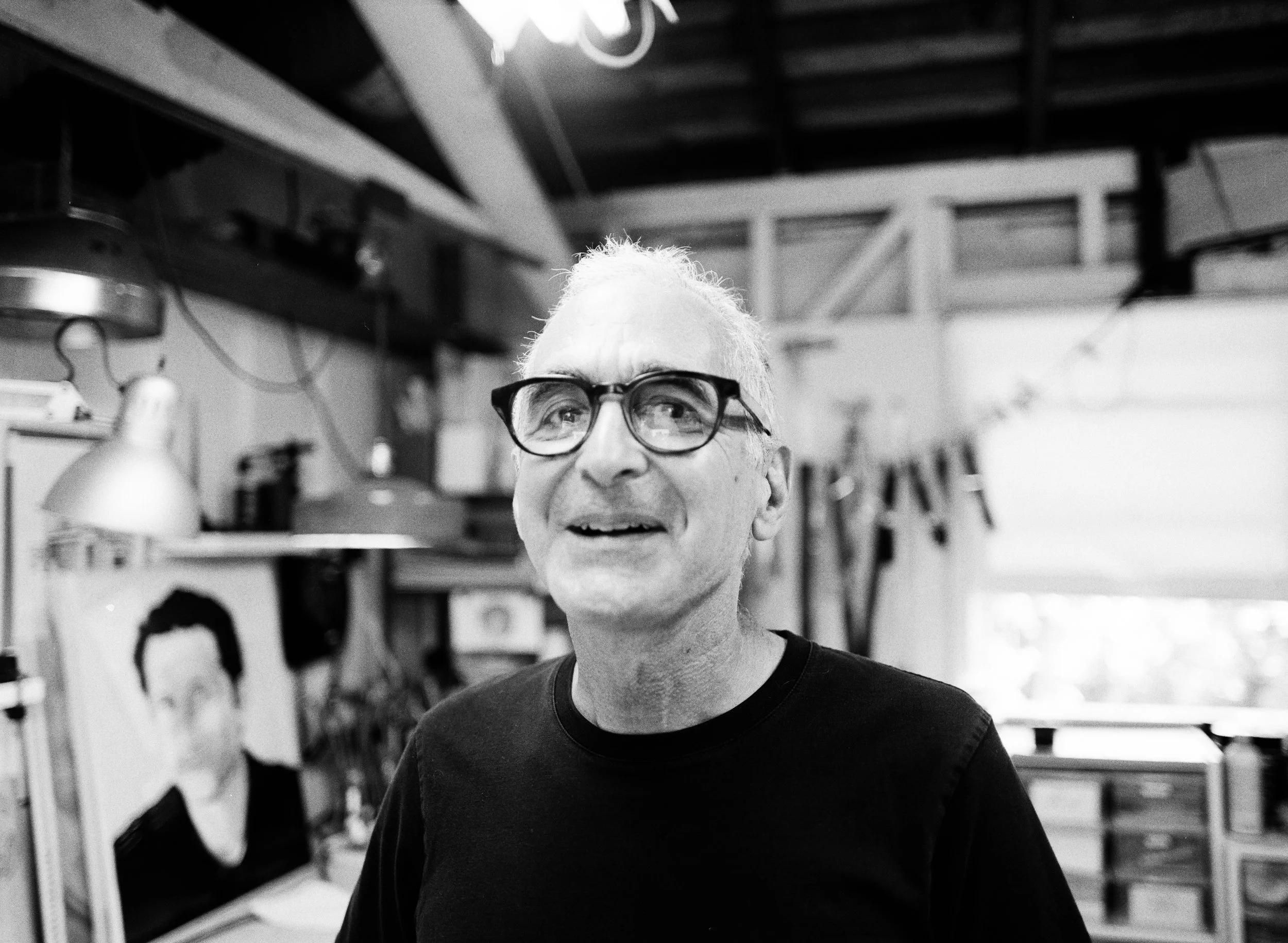

In the time I’ve spent with him, I’ve learned that his joy is in the process, not the result. Bill is an artist’s artist. He’s dipped his toes into every artistic medium possible, from ceramics to film to architecture to painting.

And in recent years, he’s allowed himself to artistically dive deep into the waters of his past. In doing so, he’s discovered that the truth lies within the colors, as they elicit deep sensorial memories, feelings, understanding.

Not only do these colors help him feel, but they help him remember.

In understanding his soul, maybe you can understand yours, too.

Welcome to Ego Death.

Airplant #3, 2025, oil on canvas, 40x53 inches

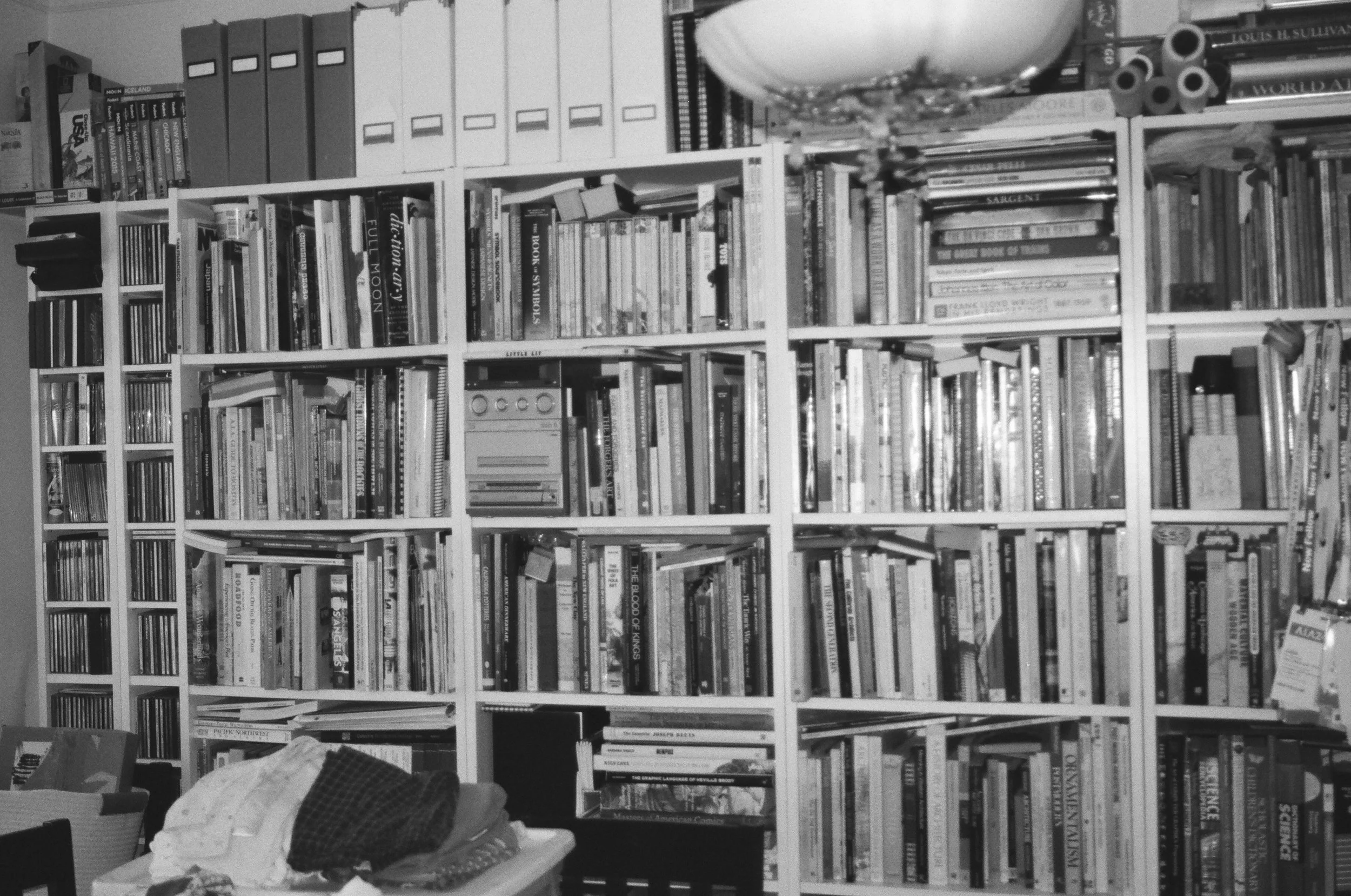

The first thing I noticed and admired about Bill’s house were the bookshelves. Not necessarily because of the quality of books, (which I don’t think I even explored), but the quantity.

I’m not sure why, but it feels like home, I told him.

“Well, that makes sense,” he inquired. “Books are basically other people. You’re there with their stories.”

As we moved outside, and sat somewhere between his garden and his studio, and discussed things somewhere between his roots and his future, I realized that he needed those books.

There was a certain terror for Bill about his childhood home. That sleepy, Sacramento suburbia with big houses and empty rooms that felt, to him, “like seeing the edge of something that shouldn’t be there.”

Comfort is the bookshelves. The maximalism. The warm embrace of stories and people.

But growing up, enveloped in this emptiness, he still didn’t really feel like there was space for him. Not because his parents were unsupportive nor unkind. While Mom and Dad worked in science and education, eleven-year-old Bill was enamored with ceramics and music.

It was unfamiliar to them.

They didn’t object, though, when Bill begged to knock on doors and sell his pottery at fifteen, or sing renaissance carols in the produce section of the grocery store with his choir group. (Who did object, though, was the neighbor who thought he was selling “pot” and the lady in a bathrobe who cared more about finding the ripest banana).

But once he turned fourteen, they stopped objecting to practically everything. Because when his seventeen-year-old brother was diagnosed with schizophrenia, there wasn’t much space left for him at all.

I tried to meet his gaze once he told me this.

His eyes whispered the gravity of this reality.

Living with someone he loved, who suffered so tremendously, was incredibly stressful for him.

It was also the 1970s, and mental health was deeply misunderstood. Most of the state mental hospitals had shut down prior to that time. There weren’t really any long-term care facilities yet. Help wasn’t accessible.

And in this quiet, suffocating town, this struggle was loud. His neighbors were even blaming his parents.

“I felt bad for my mother, the mothers get the worst of it.”

Home became too unpredictable, and it was no longer realistic for Bill to live with this parents and brother. After a failed attempt at living with his grandparents, he moved in with his best friend’s family.

“His mom was an alcoholic, but she was really nice to me. Not really to them. At all. I know this sounds really bad, but I was so relieved. It was so much better than what I was coming from.”

He found repose in the eye of the storm. It wasn’t until later that he began processing the corners of his childhood. PTSD wasn’t a stranger to him in his twenties and thirties.

With his eyes now to the ground, he shared, “I think Julia (my wife) would attest to that.”

What was he like, I asked.

He smiled, “He was also very creative.”

“When someone you love gets severely mentally ill, it’s like a big part of them is erased. They just change so much. That was the way it was with my brother. But what I also noticed was that his core personality traits miraculously persisted. While he was unpredictable in his behavior and often unintelligible, he remained at his core, kind and gentle and funny. When walking on the street, he knew most of the street folk by name, which always surprised me. He would stop and talk with them a bit, share a cigarette and a light. I mean he didn’t have any money, that’s all he had.”

What Bill always had was this passion for the process of creating.

He gives his family a lot of credit for this, actually. Not because they understood what it meant to be an artist, but because they believed religiously in education for education’s sake. Ultimately, they taught him that “the exploration of an idea is what makes life important, what makes life good.”

“My family is Armenian,” he shared. “It's a long story, but basically all of my grandparents were survivors of the Armenian genocide. So, from a very early age, [I learned] to be grateful for everything that I had, and to know that things could be taken away at any time. Except your education. There was never any pressure for commerce within that.”

This mentality was in his DNA. I mean, his initial love for ceramics was all about the exploration of a process, without any pressure to create a perfect result.

The pressure of commerce, however, was something he placed on himself. Afterall, he was pretty much on his own. And he had no role model of a successful artist.

He got into Berkeley, honoring the importance of education, and he majored in art history. However, he switched to architecture in graduate school, thinking it would serve him more of a practical purpose.

(He was confused and really just wanted to be a sculptor).

“I did learn, though, that architecture as drawn is kind of perfect, but architecture as built is not…So it's a bit of a fiction.

The imperfections are actually sometimes the greatest parts of it. And that's when I realized - I can have an idea, the idea can be perfect, but then when I'm making something, I have to give myself the freedom to change it. I had to reteach myself that after school.”

He, simply, had to refind his love for art - which was always about the imperfections and exploration of the process.

“I had a painting teacher, a friend of mine, who said - all art is like a painting. The painting is all about making adjustments. If you paint it, then you adjust. You don’t just start at one corner and then just work your way up to the other corner. I don’t know anybody who works like that.”

And while that process of readjusting rang true in his artistic process, it also rang true in his career.

I have no idea how to even begin explaining Bill’s career paths.

No, really. I mean, he’s done practically everything. (I could write twelve different articles explaining each career path, and each piece of work he’s created).

Post college, he didn’t really pursue architecture. No surprise there.

He sculpted. He drew. He co-curated an experimental exhibition furnishing the Neutra VDL House with Cold War furniture and everyday objects from the collection of the Wende Museum. He had the idea to feature objects from the east in a house from the west.

Things changed a bit when he decided to have a family with his wife, Julia. He really felt it was time to make ends meet.

So, he started a production company with his good friend and began making films. While he initially did documentary work, piecing together historical timelines in “Collecting Fragments” and riding through the ashen streets of Lahaina, Maui to document the destruction in “Fire”, he then ventured into experimental filmmaking, with impressive works like “Median,” a film paying homage to Los Angeles through a sequence of animated, satirical scenes.

There is a noticeable perspective shift between his old work and his recent work. His films now have seemingly broken all of the rules. They feature heavy concepts that swim in ticklish absurdity. But more from his perspective. More from his mind’s eye.

The ultimate proof of this shift exists within his paintings.

And as it turns out, I happened to meet Bill at a really significant time.

“It wasn’t until recently that I’ve used art to explore more difficult parts of my memories.”

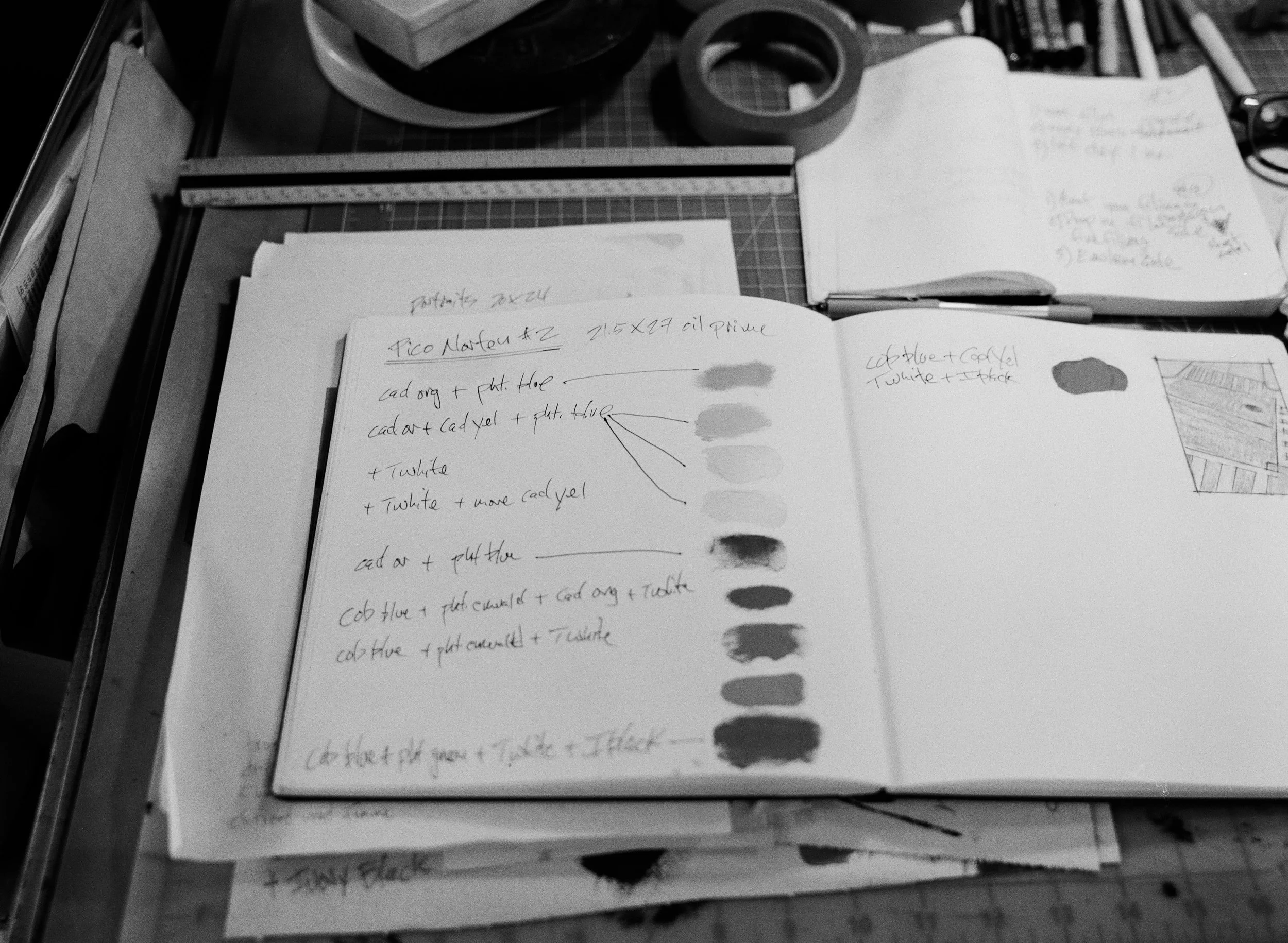

Film strips that Bill uses in his portrait paintings and experimental films.

“I feel like I'm entering a whole new phase of my work.. And I probably should have done it a long time ago. I've now given myself the permission to do it. I know that sounds really stupid, but it's -”

I cut him off. It doesn’t sound stupid, I said.

“Before I didn't give myself the permission or time and also to just say, I'm just making art now without any pressure for commerce.

I also thought that if I included the stuff that was really personal, it wouldn't: 1. Be interesting to an audience or 2. wouldn't have any sort of value, like commercial value. But I don't really care.. at this point…And I think not caring is really important. It's blinding.”

In 2023, Bill started a collection of paintings entitled House Plants. Originally, he sought to explore masculinity in a suburban environment. Specifically, the suburban environment he once knew. He approached it like he approached his documentaries - as an observer.

He hated just about everything he created. It felt impersonal. Far away. On the nose.

So, he scrapped the entire collection. It, simply, wasn’t communicating what he wanted. He knew he had to go deeper, but wasn’t entirely sure how. I mean, this was uncharted territory for him.

In order to get personal, he decided to separate himself from the narrative. He discovered that using a generic male figure as the subject of these paintings could communicate his feelings better. He didn’t need to paint himself or the suburban environment to get his point across.

“I think once I did that, that freed me up. Everything becomes more symbolic, because you’re not painting a real thing.”

So, he began again.

Window, 2024, oil on canvas, 30x40 inches

All of his true emotional realities could live within the barriers of this imaginative illustration. He wanted to create something scattered with feeling, but something that could only exist as a painting.

After creating House Plants, he began working on Air Plants, a collection still featuring a generic male figure, but floating in space as opposed to chained to the grounds of suburbia.

He sought aid from the influences of his past, though. After studying the Sistine Chapel in Rome, he grew fascinated by the ambiguity of floating figures.

“That’s why I think there’s more emotional charge to them because you're not really certain where they are in the space.”

Air Plants is truly interesting to me - because this ambiguity is intense. I’m unsure if these figures are floating due to a certain freedom, or rather, being lost.

Airplant #2, 2025, oil on canvas, 36x48 inches

Although the figure and the reason for his flight may be unspecific, this suburban environment isn’t.

And the colors aren’t.

“Somehow I suppressed how color affects my emotions and my reactions to a place - the green carpet, the brown couch, the empty taupe room. Now I am giving my color emotions more attention. I feel like I am interpreting my past through color, where colors are becoming sort of emotional codes, and they are supercharging my memories with reactions.

I have references to a lot of things in my mind. That brown relates to the brown couch we had in our living room. …When I was a kid, I remember the fucking green carpet. It was traumatic…And the same is true with that blue tape, that blue color in those paintings. It's like the painter's tape. There's something about the idea of the painter's tape being this thing that covers up some part of a house.”

Although they feature an unspecific subject, they are colored with emotion, with his own sensorial memory.

Dine, 2024, oil on canvas, 30x40 inches

Now, at this stage in his life, which has proven to be a quieter artistic exploration, this development not only aids him in completing works that feel authentic, honest, and impactful, but aids him in processing his life. His childhood.

He paints to remember.

And one thing he often remembers is his brother, who eventually found long-term care by the age of thirty, and lived there until his passing in his fifties.

“I will say, a lot of that has really informed the work that I do. In one way or another. The experience of living through it, but also how he saw the world.”

I asked him, how did he see it?

“It would be just magical sometimes…his perception of events that would happen in front of you, and how he would comment on it. How weirdly inappropriate it was. He didn’t care.”

It seems that these memories, these feelings, these colors bring him back to this freedom. This desire to create without expectation, without worry. Without need for money. Without care. With, simply, his emotional memory.

~~

I’ve been over to Bill’s house a few times since our interview. He’s shown me how to use that camera. He directed me in a short film.

He showed me his color palette.

I used to think his bookshelves elicited this feeling of home.

It was always him.